Filmmaking in the 1930s had become an insular process with no need to go beyond the studio walls. But by the mid 1940s it was as if all of the interesting and unique places and backdrops in and around Los Angeles had just been discovered. This newfound interest in location shooting was encouraged by local government officials as well. The Los Angeles Police Department, seeing an opportunity to bolster its image, began cooperating in a big way. Directors were allowed to shoot scenes inside police headquarters which in those days was located within the city hall. And J. Edgar Hoover was eager to help producers for a good plug. 1948’s The Street With No Name was among many films given access to FBI facilities.

Noir stories were all contemporary so you didn’t need special sets or costumes, the entire modern city could serve as a backdrop. The use of hard lighting and shadows in noir meant less crew and equipment was needed at a location. In the creative process of noir there would be little need for cranes and dollies. 1944’s Double Indemnity would be a turning point in this evolution. Billy Wilder’s generous use of location shots added a realism to the film that both audiences and critics took note of. The film was nominated for seven Academy Awards . Wilder was no doubt motivated by the limited possibilities on the Paramount studio lot in his desire to bring that realism to the film.

The major studio’s divestiture of their theater chains in 1948 provided opportunities for independent producers who found contemporary crime dramas to be just the ticket in terms of cost. Find a story, hire a cast and crew and go out into the environs and shoot your film. More than 80 percent of the independently produced film noirs were made after the court ordered divesture such was the impact. Many of these turned out to be very good noirs. Of course everything was much simpler in those times. There was not the maize of bureaucracy and permits that filmmakers encounter today.

Not every studio was quick to embrace the benefits of location shooting. MGM, and to a lessor extent Warner Bros, had extensive back lots and they needed to justify them. Louis B. Mayer at MGM in particular, never grasped the evolving taste of audiences nor did he have any appreciation for the new style of film making. That made MGM one of the laggards in the production of noirs. On the other hand, Warner Bros. certainly produced its share of noirs and most of them quite good despite the limitations of being filmed on the studio lot. But for any film noir aficionado the differences are not only apparent, but in some cases distracting.

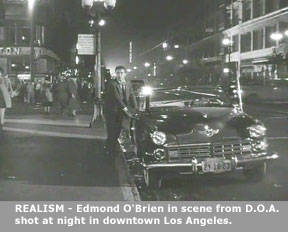

1950’s D.O.A. is an example of what location shooting did for a film. Here was a film that had an intriguing storey and good characters. However the use of locales, both in Los Angeles and San Francisco provided a realism and ambiance that could not have been achieved on the set. When watching the film the viewer is reminded at every turn the vitality of everyday life and of O’Brien’s impending mortality. It’s one of the elements that makes the film work. Conversely, The Big Sleep, was filmed entirely on Warner’s lot. It’s a classic film owing to many factors, but it has an artificial feel about it. Within noir itself there also evolved the narrative, or docudrama style of film. Films like He Walked By Night relied extensively on location backdrops to give it authenticity.

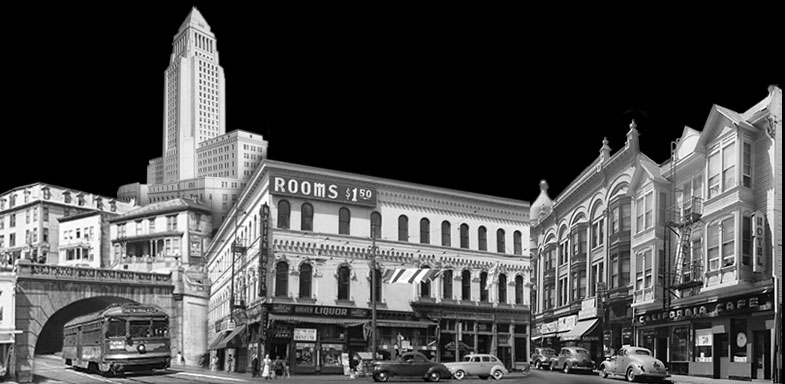

Los Angeles of the late 1940s seemed to be the right place at the right time for noir filmmakers. Raymond Chandler had already set the landscape in people’s minds using Los Angeles as the backdrop in his successful detective novels. As directors soon discovered, Los Angeles offered a wealth of interesting places for noir backdrops. Everything from the art deco Union Train Station to the boat dock at Westlake Park were finding their way into noir. But no area was more appealing than Bunker Hill district.

Los Angeles was by no means the only place directors found interesting for noir, they ventured to other cities as well. San Francisco, in particular offered the unique setting of its bay, bridges and hills. San Francisco was also a short train ride from Hollywood which didn’t bust the budget for producers. New York certainly was a natural for noir but it took bigger budgets which could not always be justified. Throughout the 1950s many of the noirs with New York stories were shot in Los Angeles using New York footage as a backdrop. Nevertheless, some producers managed to use New York in its entirety and their efforts paid off. The most definitive of these is Mark Hellenger’s The Naked City. But this discussion is about Los Angeles, a city that defined noir. Much of that fabric is gone in the never-

The film noir era is best known for the emergence of the creative style and storytelling that would define the genre. But equally important is the impact it had on the location shooting of films. When sound became a viable part of film in 1927 the studios evolved by building the large sound stages and expanded back lots so that every aspect of filmmaking could be controlled. By the mid 1930s most of the major studios had become self-

Keeping filmmaking within the confines of the studio walls also meant the studio heads could better exert their control on cost. Filming outside the studio meant extra time and increased cost. And besides, Hollywood had become quite adroit at recreating anything they needed to sufficiently convince audiences as to what they were seeing was real. The studios did maintain their library of stock footage for use as backdrops whenever they needed, but by and large the decade of the 30s saw little location shooting among Hollywood’s filmmakers. But that would change with the beginning of film noir in the early 1940s.