As much as This Gun For Hire and High Sierra changed the concepts of story content, it was only one of the elements that would come to define noir. Another aspect would be the artistic use of shadows and lighting. This technique was the hallmark of Val Lewton, the producer that RKO had brought in to make low budget horror films in 1942. His corroboration with director Jacques Tourneur on The Cat People and I Walked With A Zombie got the attention of creative types throughout Hollywood. Both films were made with very small budgets, were popular with the public and made a chunk of money for RKO. While neither film is considered noir, they nevertheless showed what could be achieved with the creative use of lighting and shadows to create atmosphere. European films had always been more expressive in their style and Tourneur certainly learned from his father, a French director of some acclaim. It would all come together for Tourneur when he was promoted to the ranks of the “A” directors at RKO and given the opportunity to direct Out Of The Past . He not only had a good cast to work with but also a generous budget. The result of course is a film that is universally recognized as one of the defining films of the genre.

It’s worth noting that the films that were seminal in fostering noir were being made at the likes of Paramount, Warner Bros. and RKO, studios that allowed a level of freedom among creative types. Meanwhile at Hollywood’s largest studio, MGM, boss Louis B. Mayer never seemed to comprehend the changes occurring around him. He continued to champion the wholesome stories and structured production methods that carried them through the previous decade. He held firm to his belief that star power was the most important factor to a film’s appeal and the director’s role was secondary. It would be some years and take a new head of production (Dore Shary) before MGM would embraced noir.

In 1944 director Billy Wilder melded the dark story of a James M. Cain novel with creative lighting and camera work to create a moody atmosphere for what would be Double Indemnity. Wilder was among a group of European emigre directors whose German Expressionism style would find its way into Hollywood. Wilder not only brought together the elements of both story and style but he shot the film extensively at locations around Los Angeles that brought realism to the film. (See Los Angeles, backdrop to noir) These would be among the defining aspects of noir. Like This Gun For Hire and High Sierra viewers were confronted with immoral characters and had to make judgements. Like the two earlier films, the ending of Double Indemnity left viewers without a sense resoluteness. Double Indemnity was nominated for seven Academy Awards, including best film, screenplay and directing, you could say it was the affirmation of noir. For the next fifteen years or so the genre would flourish.

In the late 40s economic forces would change Hollywood which would also effect film noir. The U.S. Justice Department had forced the major studios to divest themselves of their theater ownership. This provided an opening for independent producers who now had far greater access to distribute their films. This spurred production of the low budget crime dramas that defined noir and filled the now independent theater screens. Columbia and Universal studios, neither of which had owned any theaters, also seized the opportunity to devote much of their production for this profit formula.

Film noir had largely transitioned from the “A” studio productions of the 40s to the low budget films of the early 50’s. That’s not to say they weren’t as good. Quite to the contrary, the low budget, tight shooting schedules fostered a creativeness in the directors that became adept at the genre. These constraints required stories to be concise and fast paced. There was no place for extraneous romance or melodrama. The actors of these films would be made up largely by a group of newcomers as well as the second tier players cut loose by the studios in their austerity moves. This also benefited film noir with characters seemingly the average Joe’s that noir was all about. This would be the high point of genre.

THE END OF FILM NOIR

By the mid 50s television was having a serious financial impact on the studios as theater attendance fell. The studio’s response was to give theater goers what they could not get on the small screen. The studios adapted wide screen formats and theaters had been converted to run them. They were making fewer films and putting more resources into epic type of motion pictures, lavish musicals and biblical tales full of pageantry and all in vivid color. Even westerns benefited from this new focus as their expansive backdrops were enhanced in color and that genre prospered. This ultimately meant less room for noir. With longer running films came an end to the double feature which in turn meant less demand for the accompanying “B” films, a large portion of which had been noirs. In addition, many of the low budget producers had switched their emphasis to sci-

By 1960 nearly all theatrical releases were in color which effectively meant the end of noir. There would still be a trickle of film noirs -

REVIVAL

During the noir era about 400 films were made that can be classified as noir (depending on the criteria one uses). Some of the better known films like The Big Sleep, Double Indemnity, D.O.A. and Out Of The Past endured on late night television or in revival theaters. But the vast majority of noirs had been tucked away in film vaults, warehouses or in someone’s closet. Television had moved beyond the need for old black and white films and there simply were no other outlets. For 30 years film noir would be of interest primarily to serious minded film devotees or those associated with the cinema arts. There would be books written on the subject, but for most of the public, even those that claim an interest in films, film noir was an abstract term. It was like discussing an historical event in which you have to rely on the words of those privileged enough to have access to the artifacts. But that would change as technology emerged that would bring a resurgence to the genre.

By the late 1980s cable television was bringing an abundance of programing choices to most American homes. Expanding cable networks were hungry for content and for some movie channels the libraries of old noirs were tailor made. They were cheap and filled time slots. This provided an opening for many long forgotten films to have a new audience. Additionally, the VCR had become a standard feature of most homes and the film rental business came into existence. While this provided the public access to an ever increasing variety of films, the vast majority of noirs never made it to video cassette.

A convergence of factors in the 1990s would finally open the trove of film noirs to a public that had never seen them or had long forgotten about them. As cable networks refined their offerings, several networks began to feature noirs in depth. The development of the DVD changed the economics of providing content. The Internet of course facilitated the growing interest of film noir as every fan, critic and casual observer was able to share their opinion. The feasibility of streaming video has made available an additional number of films that could would not have found their way to DVD.

Despite the enormous amount of money spent on creative talent in Hollywood -

For nearly three decades most of the films that fall within the genre of film noir had all but disappeared from public view. But their significance has always been recognized by film historians and scholars. Film schools have long devoted serious study to the subject and a generation of filmmakers has been influenced. There has been a great renewed interest in the genre by those who are just now discovering that unique period of Hollywood filmmaking and the era it reflects.

FILM NOIR PRIMER Continued from main page

Any discussion by knowledgeable fans of film noir will likely provoke debate regarding the actual definition of film noir. Read any of the many books on the subject or look into any discussion group and you will find a variety of opinions. Some opine that any post WWII black and white crime drama qualifies as a noir. At the other end of the spectrum are those that subscribe to a narrowly defined set of elements both in storey and cinematic style for a film to be considered a true noir. Like most issues the answer falls somewhere in-

You might say film noir is in the eye of the beholder, but some things, at least from my perspective, are essential. Foremost, a noir is black and white. This goes to the heart of the genre. That may seem obvious but there have been a number of films made in color, which have tried to emulate noir style. Some critics have even coined the term, “neo noir”, to describe films like L.A. Confidential and City of Industry. Films that certainly make reference to classic noir in both story and style, yet lack the atmosphere that only black and white can project. Steven Spielberg recognized the power of black and white when he made Shindler’s List. The ability to evoke a sense of harshness and despair cannot be equaled in color. The best directors of noir knew this. Even though their use of black and white was dictated by economics of the time, they used the medium to create the dark atmosphere that is noir.

For most films the storey defines the genre, but with film noir it’s much more open to interpretation. That’s because in noir the style of the film is as important in defining the genre as the story itself. In fact, it has long been argued by some critics that film noir is not a genre but simply a style of filmmaking. Film noir’s linage evolved from the crime drama, so within every noir there is an underpinning element of crime. It may serve as a backdrop or it may be the focal point of the storey. Either way, it’s the common thread that usually binds the characters together in some form or another. But it’s the focus on the individual that goes to the heart of noir. And a focus that audiences had not generally seen before noir. In noir there often no demarcation between good and evil. Viewers find themselves confronted with a host of unsavory characters and are left to their own emotional devices to make judgements. This type of story was a sea change for moviegoers as noir started to flourish after WWII.

Another element that made noir different were the endings. Throughout the Depression era years of the 1930s audiences looked to the movies to provide a bit of respite from the drudgeries of the times. Indeed most of the fare during that period was light hearted melodramas with pleasant endings. Even the crime dramas were usually innocuous affairs which became known as “murder mysteries.” These were popular in series like The Thin Man, Charlie Chan, Boston Blackie and others. They were blithesome, full of wisecracking characters and had the prerequisite agreeable ending. There were exceptions of course, most notably at Warner Bros. where the gangster films ruled the day. With hard lighting, violent characters and crude treatment of women you might even say the gangster films were a forerunner of noir. But these were escapist fare with larger than life bad guys. There was a clear divide between good and evil. There was a disconnect between audiences and the gangsters depicted in these films. But in noir, the characters are more often ordinary people and their predicaments happen in real life. Fatalism is a reoccurring theme in noir and the viewer is left to ponder their own susceptibility to such events.

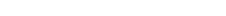

Artistic style was sometimes as important as the story itself in film noir. The use of shadows to create the dark, foreboding atmosphere is a hallmark of the genre. From left: Victor Mature -

THE BEGINNING

There is no definable moment when noir began. No director ever expressed his intent to make a noir and thus begin the genre. In fact the term did not come into use by American critics until after the genre had pretty much ended. So its actual beginnings provide another aspect of the genre that is open for debate.

The origins of noir seem to coincide with the onset of WWII. As the Great Depression of 30s ended, the benign melodramas of the that era lost appeal to audiences as the realities of a more dangerous world took hold. War movies became a focus of most major studios in response to America’s involvement in the war. For moviegoers the war films imparted a justification for violence. Audiences also were becoming more desensitized to the killing and violence from the proliferation of war films. A few screenwriters took advantage of the changing public perceptions to put forth stories that had subtle, but consequential elements that seemed to go unnoticed by censors. Among these films, High Sierra in 1941 and This Gun For Hire in 1942, both encompassed elements that would plant the early seeds of noir storylines.

In This Gun For Hire , Alan Ladd plays a cold-

With some crafty writing the viewer’s emotions are manipulated. As events unfold the viewer must make moral judgements, and everything is not black and white. We see Ladd becoming victim of a greater evil while Bogart takes on the cause of the crippled Velma and is snubbed for his efforts. It also did not hurt that both characters formed bonds with animals -